|

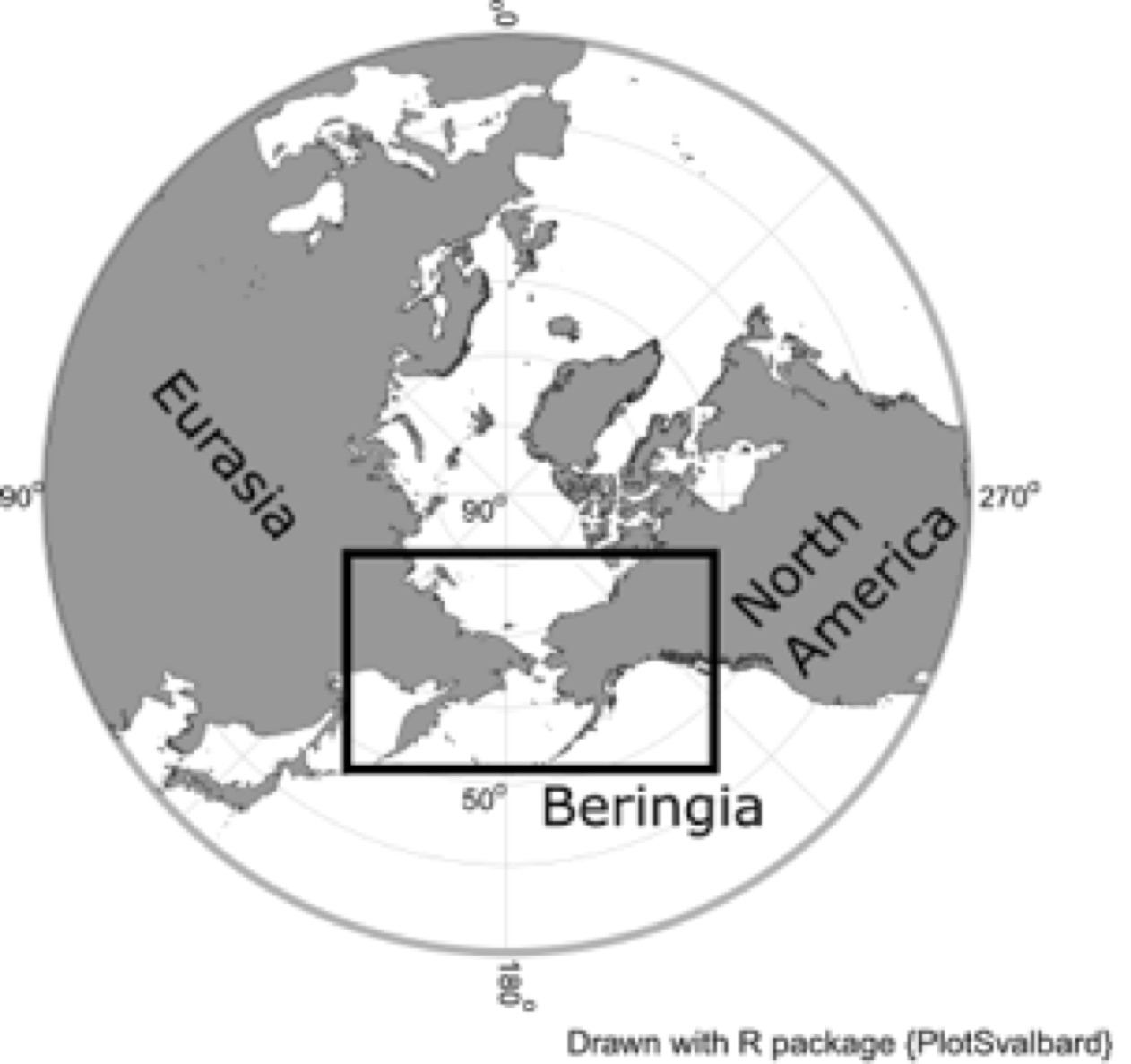

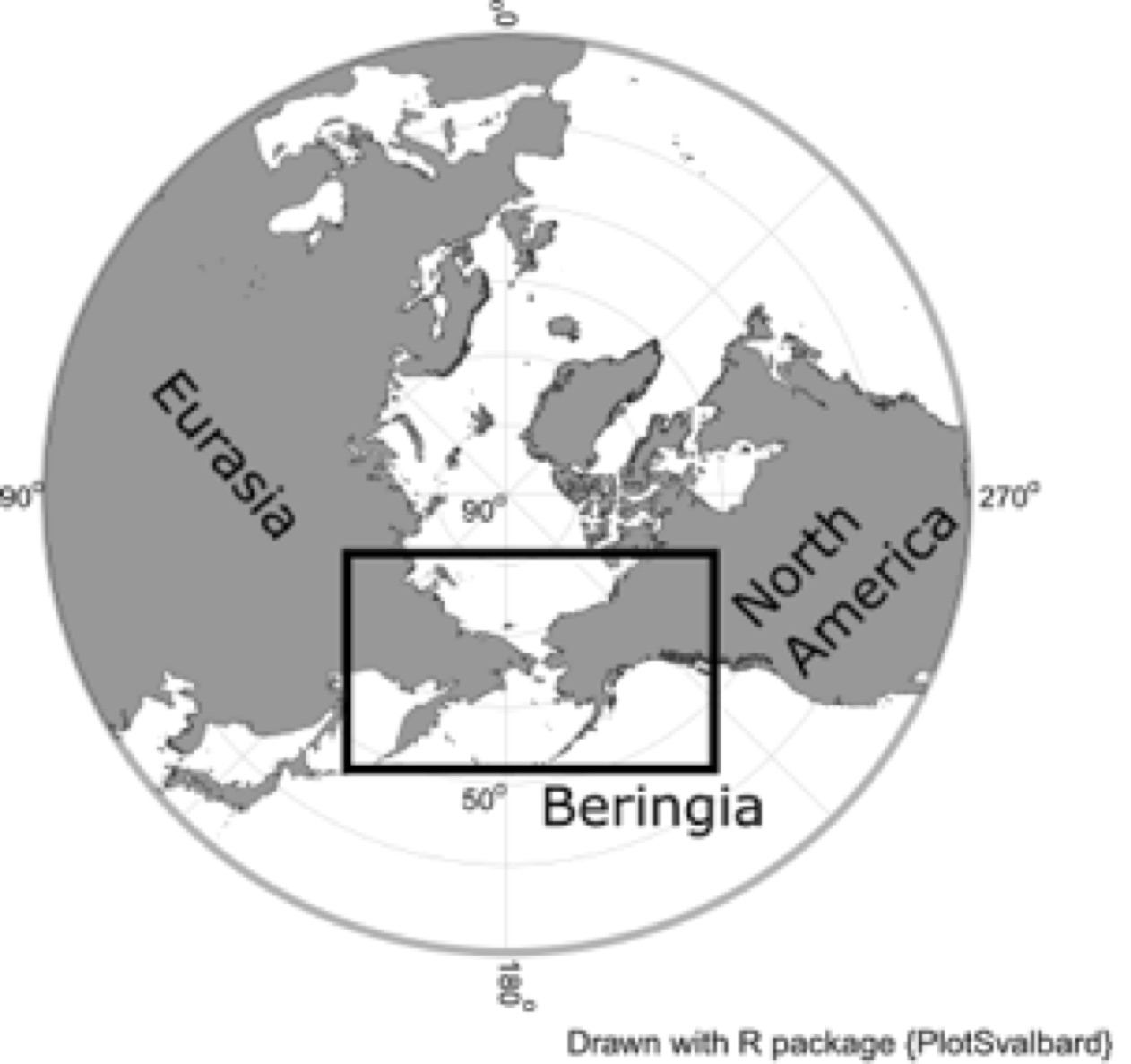

How closely related are the horses that roam the North American west today to the wild horses that lived in the same place until the end of the last Ice Age? The UCSC Paleogenomics Lab is excited to be part of an international collaboration with a goal to find out! Using ancient DNA isolated from bones and teeth from hundreds of North America’s ice age horses, we are tracing the origin and history of diversification of all living equids – donkeys, zebras, wild asses, and horses, including the horses that live today in the American West. We are focusing specifically on the hotspot of the last one million years of horse evolution: Beringia.

During past ice ages, glaciers trapped a large proportion of global water volume, which lowered sea levels. In Beringia, lower seas exposed a landmass that connected Eurasia and North America. The temporary land corridor between the continents is known as the Bering Land Bridge. The Bering Land Bridge ecosystem provided a biogeographical dispersal route for animals and plants to migrate from Eurasia into North America and vice versa. The land connection acted similarly to wildlife corridors created by conservation scientists today, but on a much larger scale and created by the geological process rather than a conservation effort.

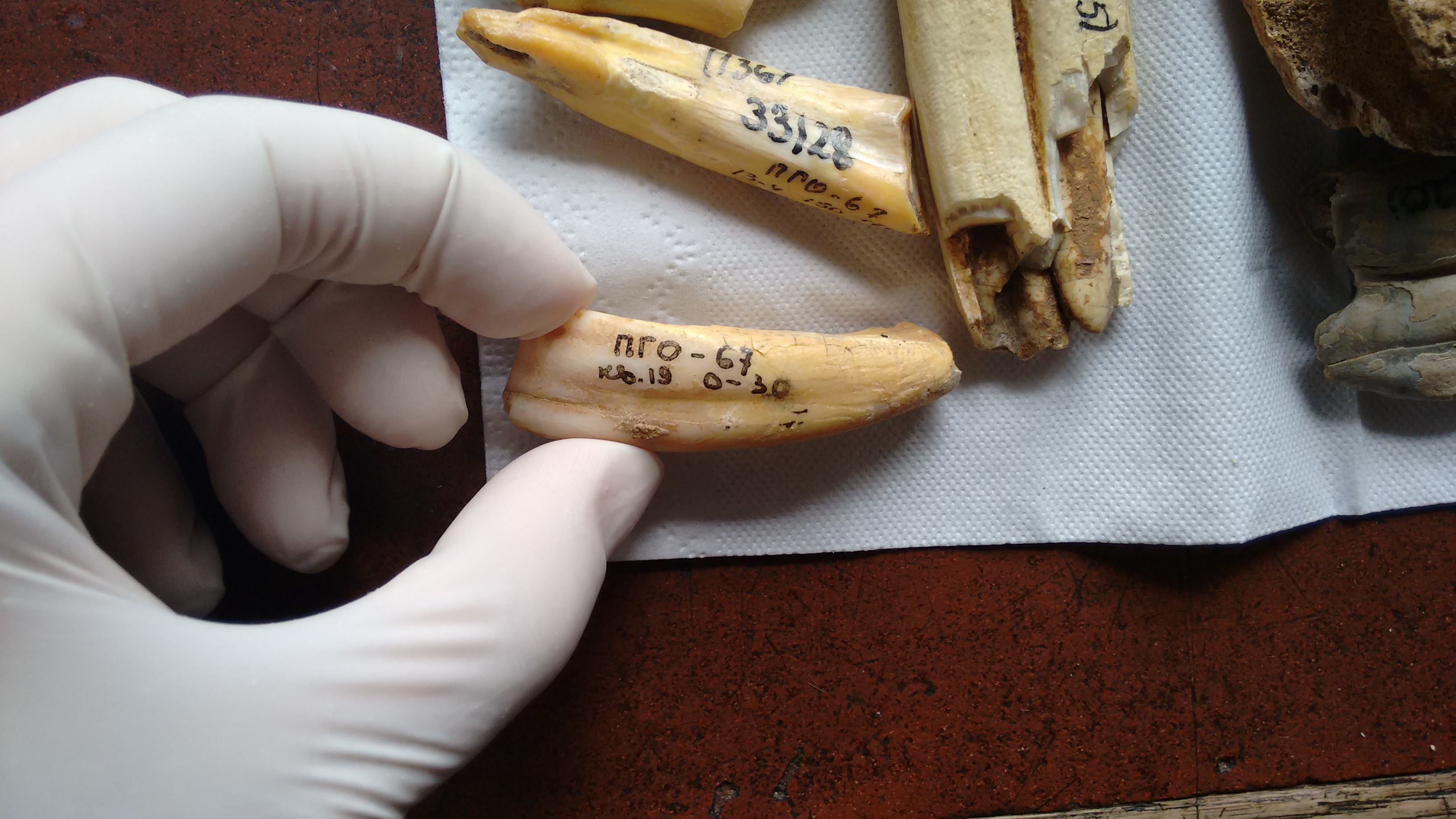

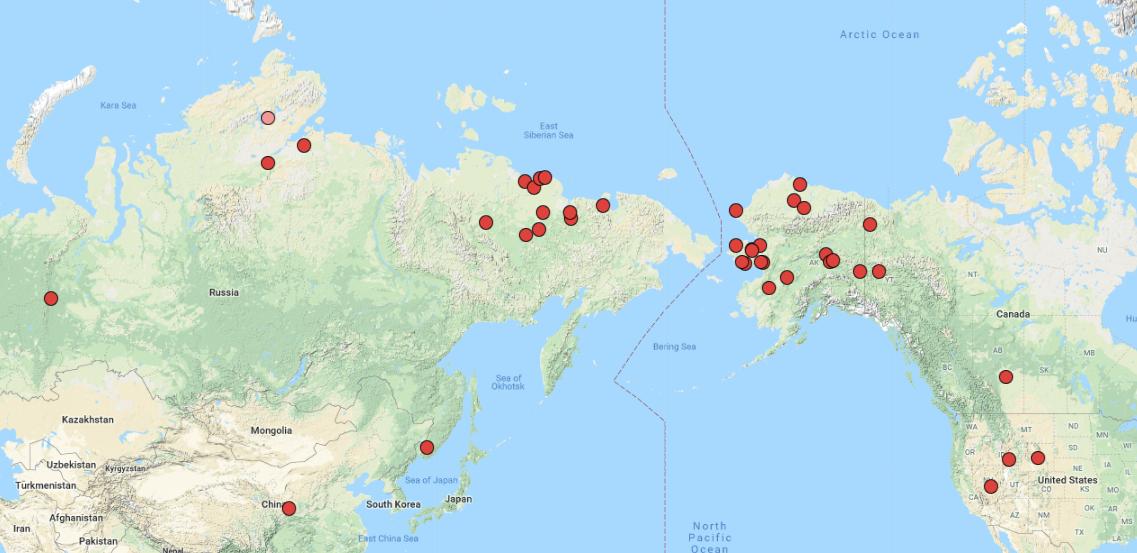

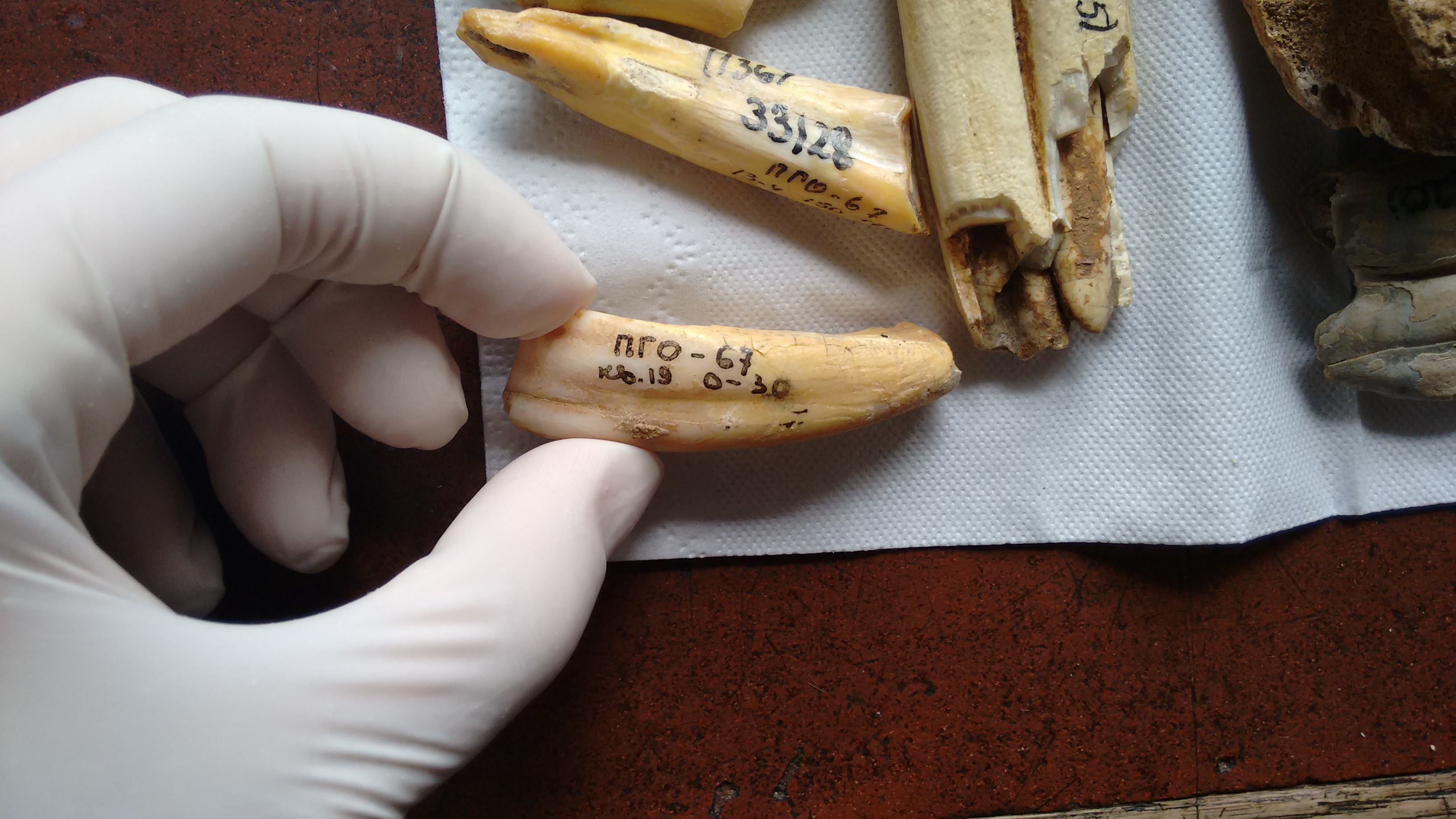

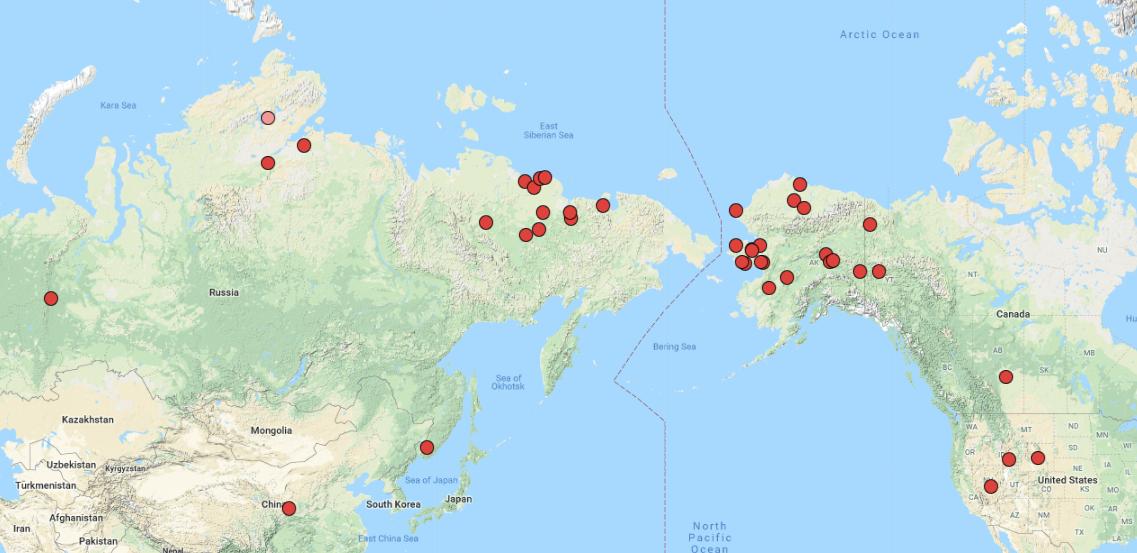

While the Bering Land Bridge probably played a critical role in horse evolution, exactly what that role was has never been thoroughly explored. Fortunately, horses that lived in the region of and around the Bering Land Bridge have an exceptional fossil record, and tens of thousands of well-preserved horse bones have been recovered from frozen soils spanning from Siberia to Yukon. Our project takes advantage of these well-preserved horse remains to explore, using DNA extracted from these bones, how often and how many horses used the Bering Land Bridge to move between continents during the last million years of their evolutionary history.

To reconstruct the evolutionary history of present-day and extinct horses, we generated ancient DNA data from a panel of more than 100 ancient horses and analysed these data using two approaches. First, we reconstructed the evolutionary history of maternally inherited mitochondrial genomes using a data set of 189 horses. The mitochondrial genomes sampled from both Eurasian and North American horse populations allowed us to estimate the number of times that female horses dispersed across the Bering Land Bridge in either direction. Second, we turned to the nuclear genomes, which, unlike mitochondrial DNA, are inherited through both male and female lines. Nuclear DNA molecules are larger and more complex than the mitochondrial ones. Thus, on the one hand, a nuclear genome is much more difficult to sequence and assemble, but on the other hand, it is more evolutionary informative.

Although our results are still preliminary and analyses are still in progress, our initial findings suggest that horses first dispersed from North America into Eurasia between 1 million and 800,000 years ago. However, the history of the horse is not so simple. After their initial colonization of Eurasia, we estimate that horses continued to disperse between the continents perhaps each time that lower sea levels exposed the Bering Land Bridge! The new immigrants integrated into the populations and shared genes, maintaining evolutionary connectivity between populations on the two continents. We found strong evidence that horses dispersed into North America from Eurasia during the most recent glacial period, not long before the colonization of North America by humans.

What do these results mean for the feral horses of the American West? The fossil record and our genetic results confirm that horses were part of the North American fauna for hundreds of thousands of years prior to their (recent in evolutionary time) extinction on the continent around eleven thousand years ago. The feral horses that roam the American West are descended from horses that were domesticated in Asia around 5500 years ago. However, early domestic horses were part of a large and evolutionarily connected population of horses that spanned much of the Northern Hemisphere. The genetic connection between extinct North American and present-day domestic horses means that the feral horses in the American West share much of their DNA and evolutionary history with their ancestors who lived on the same continent many thousands of years earlier.

Our ongoing project, Evolution of Ice Age Horses in Beringia, is a collaborative effort between researchers at the Paleogenomics Lab, the team led by Ludovic Orlando at the University Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, our colleagues Peter Heintzman, Ross MacPhee, Pamela Groves, Daniel Mann, Grant Zazula, Duane Froese, Russ Corbett-Detig, and many others. The project has been supported with funds from NSF ARC-0909456 and ARC-1417036, from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the European Research Council, and the American Wild Horse Campaign. Dr Alisa Vershinina, the leader of the project, has been further supported by the UC Santa Cruz Chancellor Dissertation Year Fellowship and a grant from the Cana Foundation. Sample collection in the Yukon region was made possible thanks to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, and the Klondike placer gold mining community.

Stay tuned for the upcoming pre-print about the results of the project!

Meanwhile, you can read more about the project here in an abstract for the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution conefrence:

Image courtesy of Sandi Sisti, Wild at Heart Images

|